March 19, 2021

Only some softly hooting desert owls disturbed our sleep during the night. The rising sun illuminated snow on peaks of the distant San Jacinto range then brightened the nearby hills.

Suddenly, the cool morning turned warm and daylight revealed the scenery that had been cloaked in darkness when we arrived. Susan figured out from Google Maps that we’d camped just a few hundred feet from the boundary for Joshua Tree National Park and the nearby trail led into the park. We decided to take a short walk to check out our surroundings.

Our walk was cut short by what we soon discovered. A walk into the wash nearby revealed that humans had disgraced the beauty of the hilly desert. A bullet-riddled No Shooting/No Dumping sign was near piles of debris that had been shot to pieces.

A washing machine and refrigerator were obliterated as was a warehouse full of glass bottles. Splintered wood littered the area along with hundreds of spent shotgun shells and bullet casings. It’s hard not to equate the mess with the pro-gun mentality and this is sadly not an unusual sight around the desert.

Disgusted, we left and got takeout coffee for Susan and a breakfast sandwich for me in Cathedral City, about 20 minutes away. Then we drove two hours to Quartzsite, AZ.

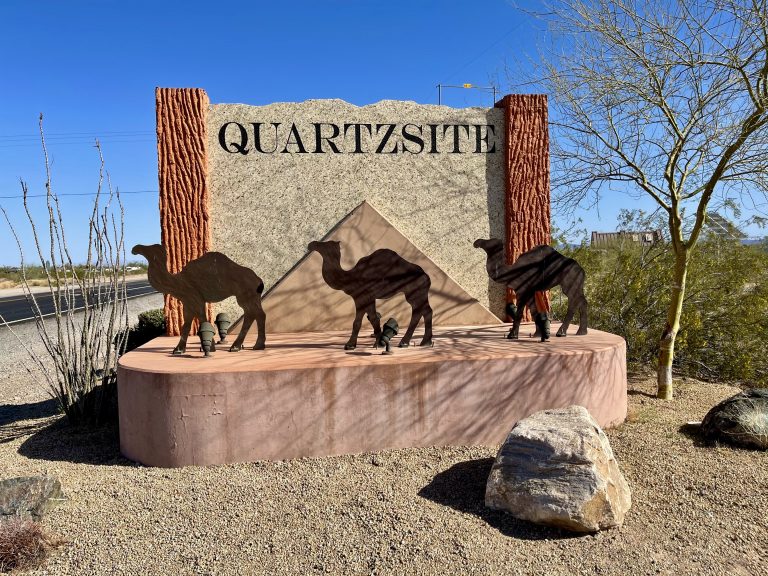

Upon arrival in Quartzsite, the first thing that struck us was the town’s sign with a bunch of camels. A little bit of history helps explain the sign.

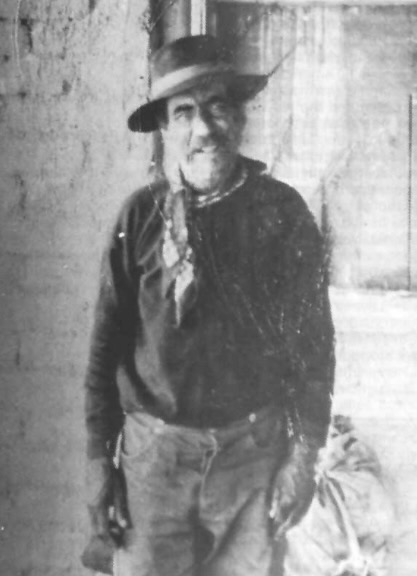

After the Mexican-American War ended, the U.S. received a huge piece of southwestern territory. The government wanted to map it and builds roads from New Mexico to California. They began building a wagon route (which later became part of iconic Route 66) but had trouble because the horses and mules just couldn’t cut it in the hot and arid rocky desert terrain. In 1857, Jefferson Davis, then Secretary of War, came up with the idea of transporting people and goods across the desert via camels, which can manage in temperatures as high as 130 degrees in the summer and don’t require a ton of daily water or food to survive. Thus began the U.S. Camel Corps. The Army imported 33 camels from the middle east, along with Syrian camel caretaker, Hadji Ali (whom the soldiers affectionately called “Hi Jolly”)—perhaps the first Syrian immigrant.

The camels could transport twice the load in half the time that horses and mules could manage, so in that sense the Great Camel Experiment was a success. However, the soldiers and civilians were unfamiliar with camels, finding them odd to ride, temperamental, and requiring very different care. And then, when the Civil War broke out, Jefferson Davis had other things to focus on and the U.S. Camel Corps was abandoned. The Army sold off some of the camels to zoos and circuses, and then freed the rest in the desert near Quartzsite. The last camel sighting was in 1942.

The second thing that struck us upon arriving at Quartzsite, also known as “the Q” (no, not that Q), was that hardly anyone was there. One initial goal for the trip was to experience the giant mass of RVs, vanlifers, overlanders and campers who make a pilgrimage every winter to Quartzsite to camp for free, or mostly free, on BLM land. Many or most are snowbirds from northern states and Canada who often come for the entire winter to enjoy warmth, comradery, campfires, potlucks, gatherings, workshops, mineral shows, and more. Coming to Quartzsite is kind of a rite of passage for boondockers. We’d heard that even during Covid the great Quartzsite boondocking convergence had brought hundreds of thousands of campers to this otherwise sleepy southern Arizona town.

Alas, we were too late. As we drove around the area, there were only scattered campers along the road; it seemed that at most 10 percent of the snowbirds were still around and the remaining campers looked forlorn. Maybe next year, we thought.

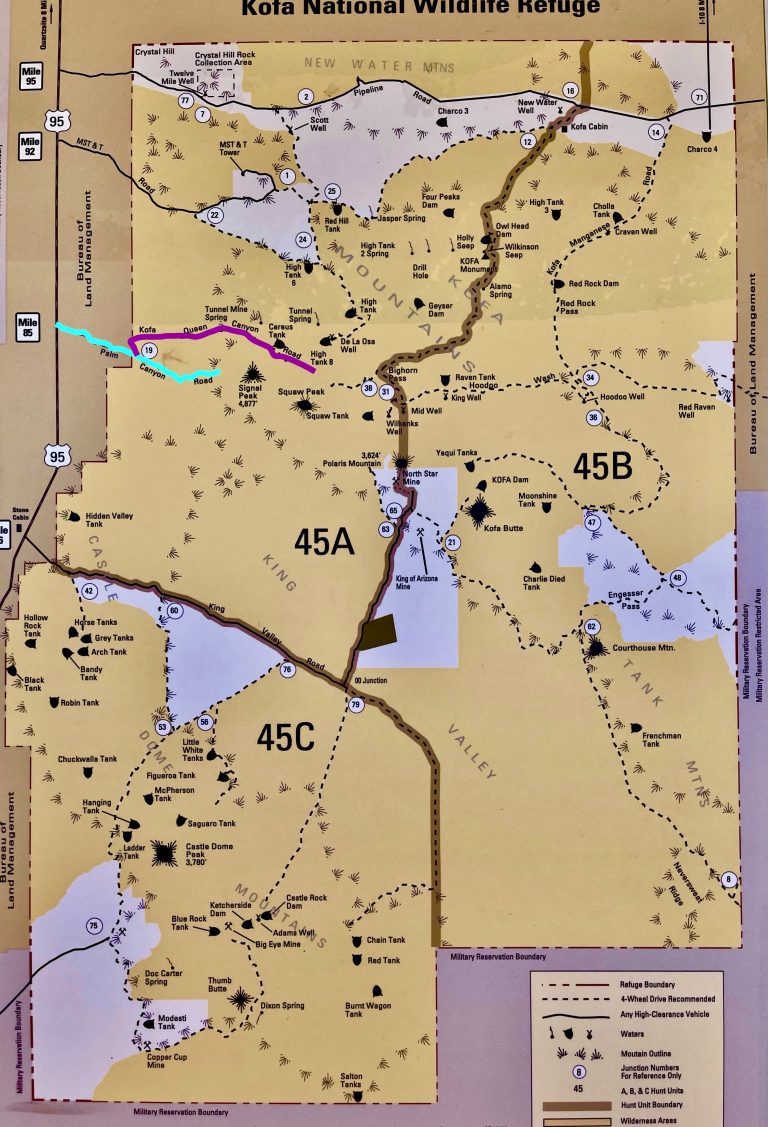

With Quartzsite having nothing much to offer, we headed south on highway 95 toward Yuma and our next destination—the Kofa National Wildlife Refuge.

A half hour later, we turned off onto a wide, dirt Palm Canyon Road, along which camping was allowed. We followed it to the end but saw no campsites we liked, as all were in open areas and too close to the dusty road.

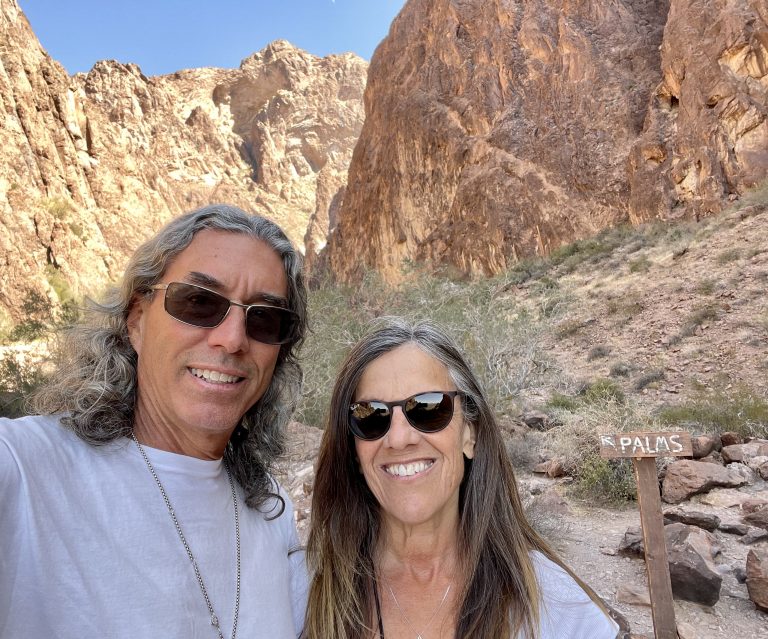

At the end of Palm Canyon Road was one-mile out-and-back Palm Canyon Trail that led into the Kofa Mountains and where there was said to be one of the few remaining stands of the California Fan Palm.

When we arrived at the trailhead, we met a young vanlife couple who’d also come to Quartzsite hoping to see the spectacle of hundreds of thousands of campers.

It turned out that the woman was from Washington, DC and we enjoyed chatting about our mutual former DC lives and hearing about how she’d left DC mid-Covid and become a nomad with her boyfriend. Though we missed out on meeting throngs of people in Quartzsite, we patted ourselves on the back for having met at least one vanlife couple.

At the end was a small sign saying Palms, with an arrow. We looked and sure enough, a few hundred yards away clinging high up on the side of the mountain in a steep chasm were a few dozen beautiful palm trees, looking like they’d been transplanted onto sheer rock. The green contrasted with the light and dark brown rock, and the dazzling blue sky above made the palms seem completely out of place.

The whole area in the mountains felt intimate and peaceful, even spiritual, as we sat on some rocks looking back at the desert for a while to absorb it. Big Horn Sheep lived in the mountains but sadly we saw none.

Back at the truck, we looked at the map and decided to backtrack down Palm Canyon Road a few miles to where we’d seen a narrower road (Kofa Queen Canyon Road) marked 4×4 Only. We followed the rough narrow road for about seven miles, where it passed into the same mountain range we’d just hiked in, but from a different direction. Along the way we saw several good campsites.

Where the road entered the mountains and became a sandy wash, we turned around because we wanted to see the mountains rather than be in them. About a mile back, we found a large campsite off the road.

The campsite was large, flat and filled with small brown and black rocks that looked like they’d been burned and shattered in the heat of the summer. Fuzzy-looking (but not) cholla cacti, ranging from ankle to waist high, sprouted intermittently around the rocks, waiting for an errant ankle to impale. We tried to take note of where they were around the campsite.

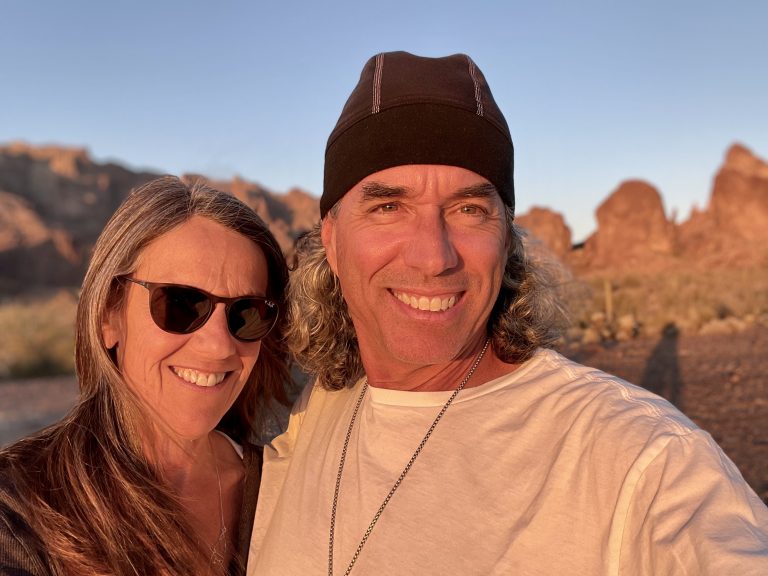

We set up table and chairs and reveled in the 85-degree sun as a light wind sprang up (hence, the hats).

After dinner, we took dozens of pictures as the setting sun lit the chollas, the mountains and us, changing color every minute. As darkness descended, a couple of trucks trundled by looking for camping spots. Then it was as quiet as only the desert can be.

One Response

I always enjoy your story-telling and the photos – they are particularly beautiful in this episode.