January 23, 2022

We’d prearranged for a private guide today to pick us up at 7:30 am and take us a couple hours away to a place called Piedra del Penõl, the surrounding reservoir, and the nearby town of Guatapé. We had a light, early breakfast, since the tour included both breakfast and lunch. Our guide arrived exactly on time and we were surprised to see he drove a minivan—large vehicles are rare in Medellín, and a minivan is even more unusual. Luis, our driver, was large and gregarious and spoke decent English, having lived in Miami for a few years before returning to Medellín, his hometown. As we left the city, he explained how Medellín had grown but that further growth would be limited because most of the steep sides of the valley had already been developed.

A nine-kilometer-long tunnel took us out of the valley and eventually we stopped for breakfast at a small outdoor restaurant along what seemed to be the only six-lane highway in the area. As usual, the weather was fantastic, with highs in the low 80s and scattered clouds. Aside from some more rain in the wet season, this, according to Luis, was how every day in the Medellín area was—perpetual spring.

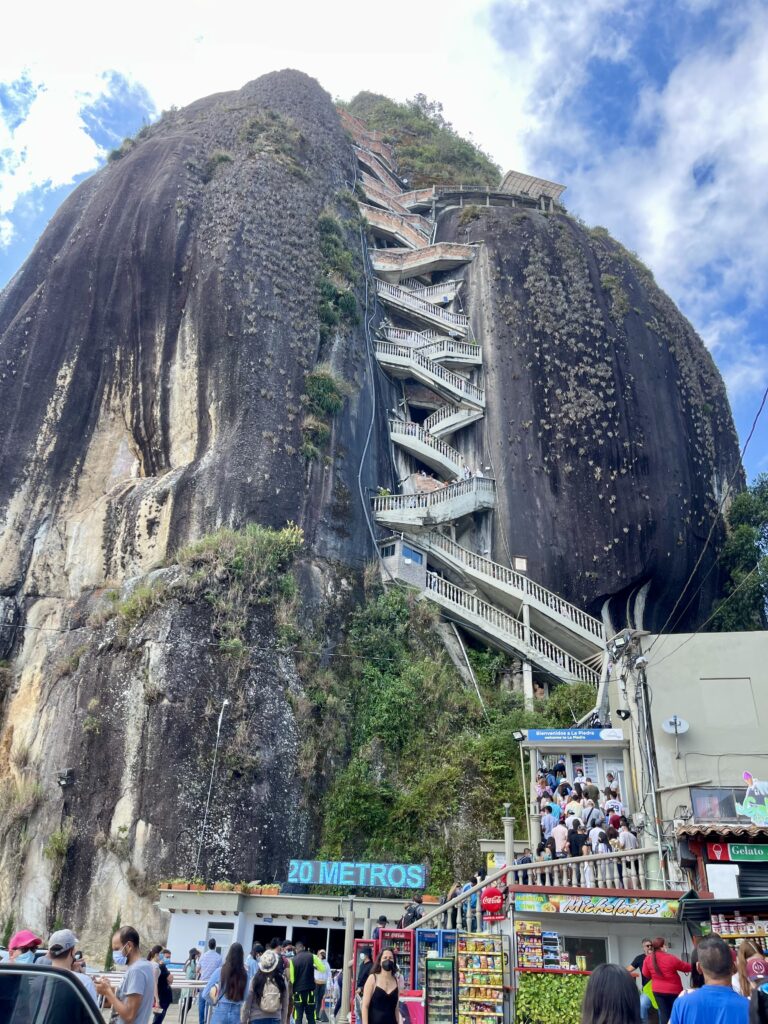

We continued until we crested a hill and saw 650-foot high El Peñón, a huge rock near the edge of an enormous man-made lake. It reminded us a little of Morro Rock near Morro Bay California. Years ago, someone bought El Peñón and installed wooden stairs on it and charged tourists to climb it. Eventually, the owner replaced the wooden stairs with concrete.

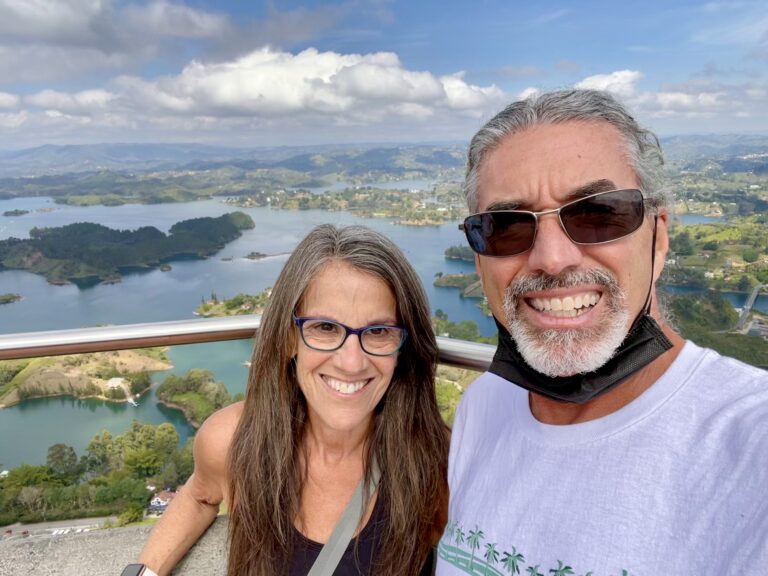

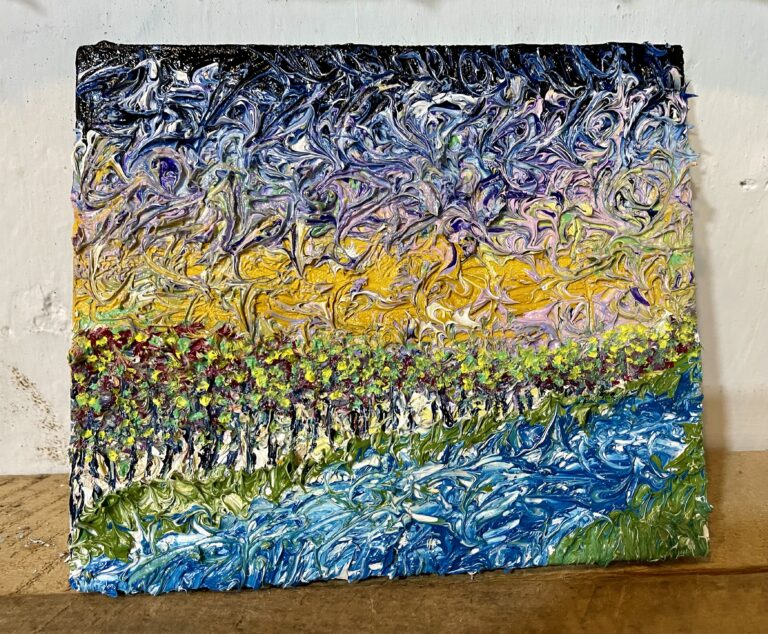

Seven hundred and eight steep and uneven steps later, we made it to the observation area where the stunning geography of this part of Colombia spread out before us. Small and medium sized mountains marched away as far as the eye could see, covered in dense greenery.

Even more spectacular was the view of huge Embalse de Peñol, one of the largest reservoirs in Colombia, winding for miles and dotted with islands. The reservoir’s meandering shoreline is dotted with expensive homes, many of which we learned belong to U.S. ex-pats.

Back down the steep steps, we met up with Luis who was waiting for us at one of the restaurants near the base. There was now a line of tourists waiting to climb the rock and the parking area that had been mostly empty when we arrived now was filled with cars. Luis told us that, especially this being a Sunday, the crowds pick up substantially as the day goes on—which was why we’d begun our tour so early.

As we drove off, Luis explained the history of the reservoir. Thirty-something years ago, the government decided to dam the Guatapé River to create a hydroelectric powerplant, which now powers a third of Colombia. To build the reservoir, the government flooded the entire town of El Peñol, which used to be adjacent to the rock and now is underwater.

The government built an entirely new town of El Peñol a few miles away and relocated the tens of thousands of residents who’d lost their town, mostly against their will, as they’d lived and farmed there for centuries.

En route to our next destination, we drove through the modern-looking new town of El Peñol, complete with its own replica of the rock. Luis told us that the new town was in many ways nicer than the old town had been, but to us it lacked character and, obviously, didn’t have the real rock.

We continued the tour in a boat, which took us on an excursion of the twisting reservoir. In the middle of one arm, a giant cross thrust out of the lake in the exact spot where a large church used to be in the original town of El Peñol before it was flooded. Luis explained that an underwater tower supports the cross. It was a sobering reminder of the doomed town.

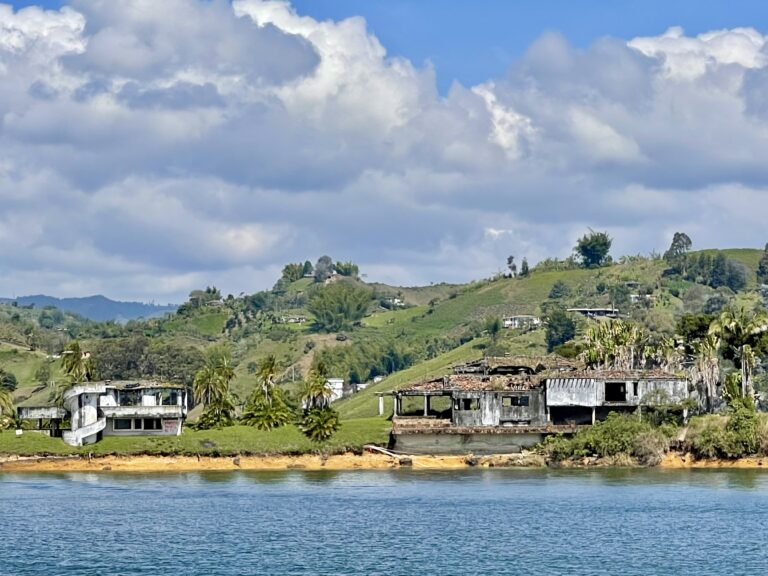

Farther along the shoreline, Luis pointed out one of Pablo Escobar’s mansions—a lavish estate he called La Manuela. This once-beautiful compound set on a stunning point on the lake had once included a stately mansion, a complete discotheque, pool, tennis courts, helipad, seaplane dock, stables, a guest house, and trees imported from around the world. Ultimately, one of Escobar’s enemies planted a bomb that destroyed most of the structures, though Escobar was not in it. The bombed-out compound still stands as testament to the violence of the Medellín cartels. The structures have since been repurposed as a paintball venue.

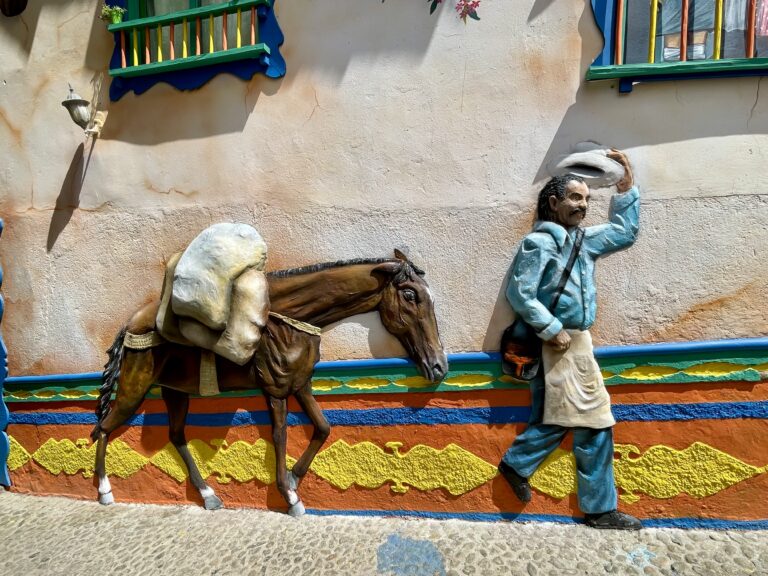

Before returning to our minivan after the boat ride, we climbed up a small hill to Parque Temático Réplica del Viejo Peñol, a replica of the main square of the original town of El Peñol perched above the lake. Apparently, the government’s guilt about destroying the town not only led to building a replacement town but also to creating this little tourist attraction, complete with a duplicate of the village church plus lots of souvenir shops and cafes.

Luis bought himself and Susan a couple of exceptional espressos at one of the fake town’s tiendas before we continued to the final stop on our tour—the small town of Guatapé. As we approached, we were surprised by the heavy traffic. Undeterred, Luis knowingly parked in a nearly full lot outside of the town.

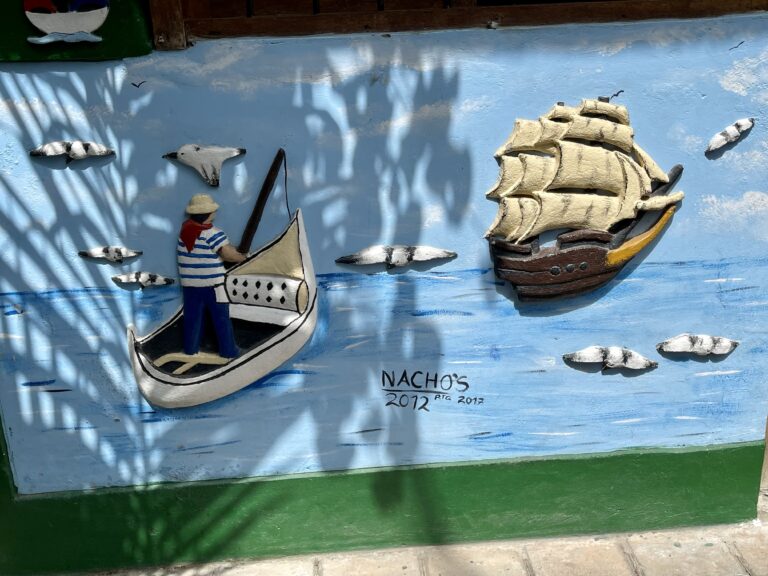

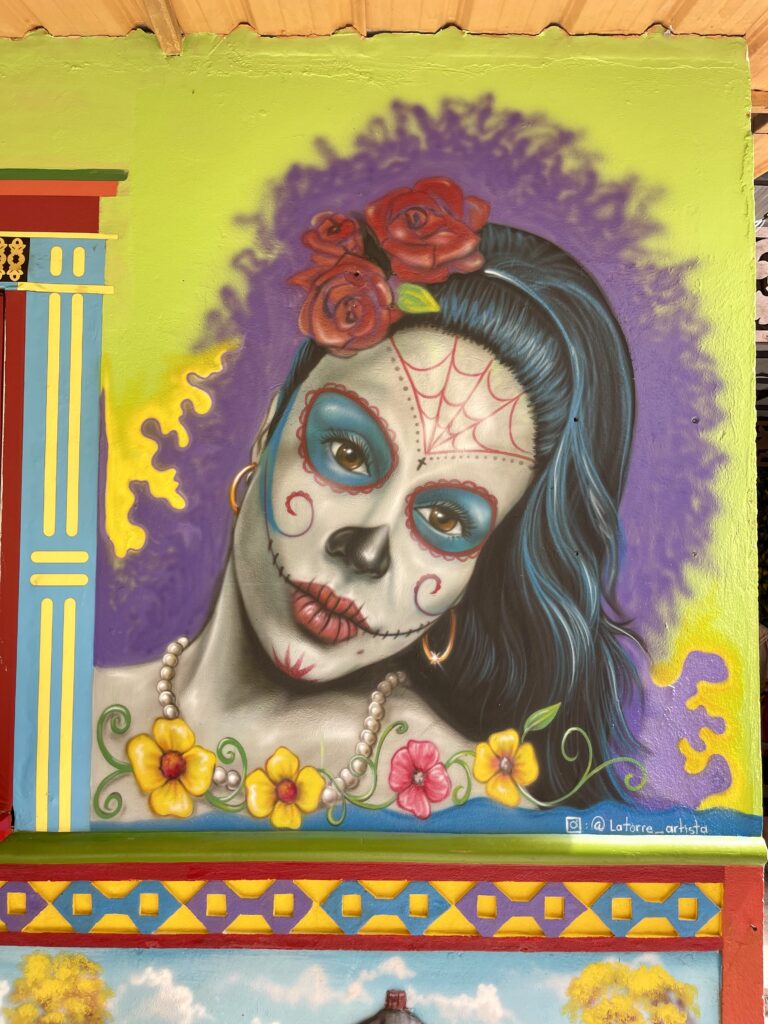

Luis explained that tourists from all over Colombia (and elsewhere) flock to Guatapé to see its intricate zócalos, which are three-dimensional friezes painted with bright colors on tiles and typically embedded along the lower walls of each building.

It’s not clear why the zócalo tradition began, but Luis explained it had been around for about a century and it’s rigorously maintained because it helps keep the tourists coming. In fact, every building owner is required to have them and the state government gives each owner a million Colombian pesos (about US$250) to decorate their homes and businesses.

The entire small town felt like a work of art and we delighted in walking along the narrow streets admiring the vivid designs and lively scene.

We also wandered briefly along Guatapé’s waterfront promenade where tour boats lined up to bring tourists out on the water. Many were not currently operating due to Covid.

After our stroll along the waterfront, Luis brought us to a small restaurant where we sat outside and enjoyed a lunch of fresh-caught fish from the lake.

The Sunday tourist traffic was pretty heavy leaving Guatapé and passing El Peñón again on the way back. Then, as we got closer to Medellín, Luis had to contend with the usual slow trucks, crazy fast motorcycles and Colombian tourists trying to get home. I was glad I wasn’t driving though I couldn’t help wondering what it was like to drive a diesel minivan with a stick. On the way back, Luis bypassed the mountain tunnel and this time we went over the mountain to give us a better view. From 8,300 feet, we could see the beautiful city of four million people below, with tall buildings scattered in clusters and thousands of red/brown brick buildings climbing the sides of the enormous hanging valley. The steep highway down taxed our brakes as we descended into the city.

Back at the hotel, we decided to walk nearby for a light dinner. After two breakfasts and a large lunch we didn’t want much. We found nearly every café was closed and street food vendors weren’t out at 6pm on a Sunday. Instead, we went into a large grocery store by our hotel and bought a few items, including some chocolate-filled bakery treats that were even better than the ones we’d enjoyed in Minca.

One Response