February 3, 2022

The day dawned cloudy unlike previous days. The wind had changed from the west to the east. At home such a change from the north to the south meant rain and we figured we’d see some today.

After breakfast, Jón said the staff would like to wash any dirty clothes we had and we jumped at the chance. We knew there was no washer or dryer within miles of us and assumed they’d wash them all by hand. With the intense humidity, we didn’t know how they’d dry.

Once again in our smelly and dirty jungle gear, this time with rubber boots, we set in the boat off for a lowland jungle hike that would start about two miles upstream. Soon, we pulled up on the riverbank. As usual, Saul was point man with his machete and he immediately began hacking his way through dense jungle until we dropped into the lowland jungle that had much less underbrush.

It was probably barely 90 degrees out but very muggy as we stopped at a small pond with enormous lily pads, some five or six feet across. Jón explained they were the largest lily pads in the world and that sometimes two-foot-long baby caiman climbed onto them to sun themselves. Underneath they had spines to keep animals from eating them. One of the lily pads was flowering an Jón told us that a certain type of beetle was attracted to the flowers. It would climb inside at night and the flower would close over it until morning, imprisoning it and forcing the beetle to pollinate the flower before releasing the beetle the next morning. A pollinated flower changed color overnight.

Nearby, Jón pointed out a large Hoatzin (pronounced hwat-sin) bird on a low branch. This pheasant-sized bird, he explained, was nearly prehistoric. The baby birds had claws on their wings and would throw themselves out of the nest when threatened, bounce on the jungle floor and then when it was safe, use their claws to climb back up the tree to the nest. The adults’ huge crest and ungainly flight made them look like small dinosaurs.

Saul’s machete rang out as we moved through the jungle toward a slow-moving creek. We made our way through a maze of trees with dozens of above-ground roots and long hanging vines. Just as Susan mentioned that the vines seemed perfect for monkeys to swing from, Jón pointed out squirrel monkeys in the trees above us, spectacularly leaping from branch to branch. One monkey had a baby on its back as it leaped!

Soon, it started to lightly rain, slowly building in intensity until we put on our cheap vinyl rain jackets, making us even hotter. The jungle had obviously grown since the last time Saul and Jón were here and the going was slow through the dense trees and undergrowth.

At one point, Saul, ever vigilant, stopped in his tracks and made sure we all avoided getting too near an enormous beehive on the jungle floor along the path. Saul tried to get some of the honeycomb but soon thought better of it.

A few minutes later, Saul spotted a two-toed sloth skeleton on the ground from which we took some of the claws as a souvenir. Then Jón picked up an enormous snail shell which Susan kept as a second souvenir.

As we slowly made our way around the loop “trail” (it was more like a create-a-trail-with-a-machete-as-you-go) in the light rain, a bright red flower appeared. It hung from one of the many vines in stark contrast to the green and brown of the jungle.

We looked it up later and learned it was a Scarlet Flame Red Passion Flower. Though the plant produces edible passion fruit, the flower and roots contain cyanide as well as a unique slower-acting poison, and it’s one of the most poisonous plants in the world. We thought about the bright red poison dart frogs we’d seen a few days earlier and decided bright red in the Amazon jungle is a warning to heed!

Eventually, we made it back to the boat and motored slowly to the lodge, Saul and Jón were soaked with no rain gear but were perfectly content. But we had no idea how we or our clothes would dry out. Most days we took at least three cold showers and the two small towels never dried.

After yet another huge lunch, Jón offered that after siesta he’d take us to the nearby village of Oran, where he was born and where Saul still lived. We jumped at the opportunity. While we showered and rested, the rain let up.

We walked along the dirt trail that connected the lodge to the village, about a 15-minute walk. Oran was one of the largest villages in the area, built on the banks of the Amazon and home to about 500 residents.

The first residents we saw were a couple of teenage girls, one with a baby, which we assumed was hers. Then we passed a soccer field just before the village where a dozen barefoot teen boys played Peru’s beloved game.

Just after crossing the bridge, two adorable little boys came running up to greet us. Their mothers were nearby working in a small tienda and we got their permission to photograph the boys, who were mugging for the camera Susan had out.

As we walked through the little town, we were surprised to see perhaps 7 or 8 such stores. Each was nominally stocked with snacks, other foods, and a few household products. We saw no customers enter any of the stores and couldn’t imagine how the tiny town could support that many stores or how the proprietors could make a living.

Jón said most of the villagers farmed or fished for a living and occasionally took the boat bus to Iquitos to sell bananas or other produce. There was a buffalo ranch nearby that made cheese (one meal at the lodge included fried buffalo cheese, which was surprisingly tasty). There was no industry in Oran. People lived very much like they did before the Spanish arrived centuries ago but now they went to church and wore T-shirts and soccer garb. All the people we saw were small and stocky, like Saul.

The village was obviously extremely poor. There were no roads, and no cars, but a couple of wide paved sidewalks with trenches on both sides. Nearly all the houses were wood, some with thatched roofs. Termites were a real problem here and Jón said the buildings didn’t last long. Curiously, none of the houses had glass windows but instead they just had window openings. Screens were not a thing, presumably because, like Jón and Saul, the rest of the locals had developed immunity to mosquitoes.

We asked Jón if the residents owned or rented their homes. He explained that people owned them but didn’t have to buy the land. Instead, they would select a lot they wanted and the government would simply give it to them. Then it was up to the residents to build their houses. Because the Peruvian government felt the villagers got few advantages from Peru, and because most of the Amazonas residents lacked formal employment, they also paid no taxes.

Modern steel power poles with lines had been constructed and connected to many buildings many years ago, but Jón said there never was never any power. Most houses had a single solar panel and battery for lights though some even had a Direct TV antenna. There was a huge microwave tower in the center of town for phone service but no internet.

The small village somehow supported multiple churches. They were scattered about the village and included a variety of demoninations.

Oran had a school for children up to age 12. People who lived in the scattered houses we’d seen along the river brought their children to Oran for school too, as there were no other schools anywhere nearby. After age 12, any children wanting further education had to move upriver to Iquitos, the big city hours away by boat. Jón said that the boat bus to Iquitos cost about $4 for the eight-hour ride. He had gone there for school, living with extended family.

Healthcare at the new clinic was provided by a single nurse who worked there only for about three hours a day, M-F. Care was completely free. If more extensive care was needed beyond what was available at the clinic, patients had to go to Iquitos. Jón told us that he could sometimes sort-of get a cell signal from the tower near the medical center. It definitely didn’t provide any service for us.

Saul showed us his house, located near the medical center. Then we headed back through the village past where Jón’s family lived. In front of his family’s house, young girls played volleyball in the street—they were all very good.

A couple of young girls rode beat-up bikes on the sidewalks. They grinned as they came toward us. People were friendly throughout the village, though we felt like intrusive, tall gringos. Ever-present Saul still lived in the village and knew everyone and, it seemed that as we walked, he helped explain our visit to the villagers and how good it was for the local economy. Jón told us that the lodge where we were staying was the largest (and maybe only?) local employer.

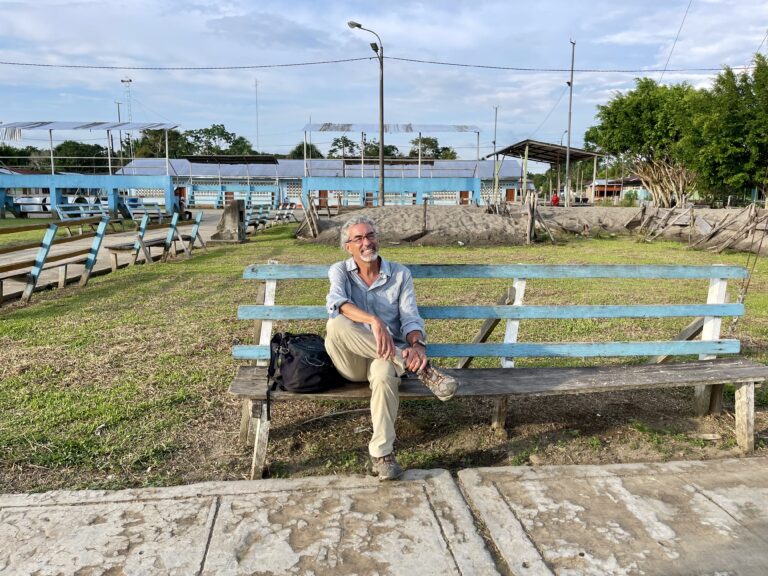

Rounding out our tour of the village, we headed to the riverfront. There was a pretty park area with palm trees and park benches, where Charles sat to take a break. Jón told us that the riverfront area was all fairly new. Ten years before, erosion had forced the entire village to move back several hundred feet. It was likely that eventually the village would have to be moved again.

Though the town sign referred to a marina, there wasn’t one to be seen. Apparently, when the boat bus or other craft arrived they just pulled up along the shoreline. There was a small bar overlooking the water in one of the nicest spots in the village. A number of pecky peckies and non-motorized craft were sitting along the shoreline near the bar.

As impoverished as they were, the residents all seemed happy. There was no traffic, no social media and no 9 to 5. They were in such a remote location that they’d had just two cases of Covid and both were mild. Vaccines and masks were not part of life in Oran. (Though we were vaccinated and boostered, we felt like we were the biggest Covid risk to the locals).

Back in our cabin after another excessively large dinner, we discussed how we wished every American could visit a village like Oran to understand the advantages we have, even when we’re stuck inside our own first-world problems. The poorest Americans were wealthy by comparison. The villagers in Oran had no safety net, no social security and no representation, but they had family and were happy.