August 27, 2022

In the morning, we woke to light rain but soon after the rain cleared we could see other rain clouds 20, 30, 50 miles away, so high were we and so clear was the air. We weren’t ready for breakfast, so we left shortly after getting up, eager to continue the drive north.

On the first couple hundred miles of the Dempster yesterday, the road had ranged from bone-jarring at 20 mph to reasonable at 40 mph. It had been like a video game: dodge potholes, miss washboard, steer around gravel heaps, shoot spaceships… The road had taken all of my concentration sometimes so I could barely see the views.

When we started out today and left the hills behind, the road improved. Soon, we were traveling at 50 mph and I had to avoid potholes only every couple of miles. It wasn’t long, however, before the road deteriorated again. By now, the truck was caked in layer upon layer of mud/dust/rain. How thoughtful we mused, Canada is applying a protective coating to our paint.

We stopped for gas at the Eagle Plains gas station and repair shop, the halfway point to the Arctic Ocean from Dawson City. Gas was US$6.50 per gallon but they could have charged almost anything. We had the capacity to make it all the way from Dawson City to the Arctic Ocean but not with enough reserve so we topped off.

The attendant was a dirty middle-aged man with long red scars along both cheeks and his swollen right-hand knuckles were wrapped in electrical tape. He was by himself and I wasn’t sure what he did all day with only a dozen or so cars stopping by. While he fueled us up, I asked him what was the most common breakdown. “Tires!” I figured that. What else, I asked. “Crazy, but running out of oil. Oh, and the road shakes spark plugs loose. Once they get blown out of the cylinder, I can’t fix ‘em.” Okay. So, what then, I asked. “A tow back to Dawson City. About four thousand dollars. Then you’ll wait a month until they can get to you. AAA don’t cover none of that.” I thought that if we had a breakdown a hundred miles from here, money might not be our first worry.

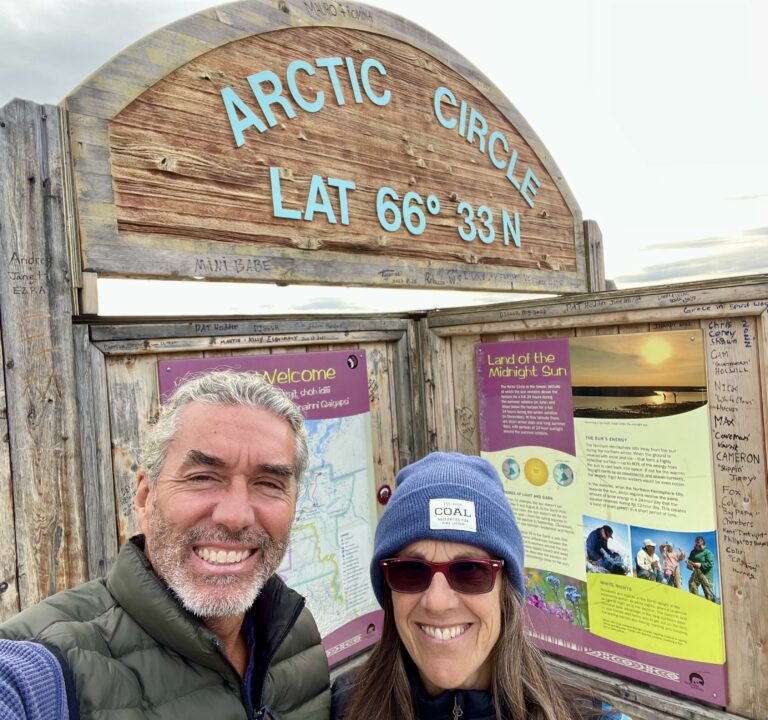

Around mid-morning, we came to a pull-off with the sign we’d been waiting for. The Arctic Circle! The views were expansive as we were now on the tundra with few trees. Here and north of us there was 24 hours of sun in summer and 24 hours of darkness in winter. In fact, we were confused by the sun the night before as it didn’t really set at all, it just moved across the sky, then below the horizon, but it’s loom was easily visible at 2 am.

After the Arctic Circle, the road twisted and turned again for mile after mile. The scenery was a colorful autumn tundra under an overcast sky. Mostly today was about getting more miles in as we drove ever-closer to the Arctic Ocean. Sometimes the gravel was good, sometimes bad. Traffic was almost nonexistent except at a couple of ferries where three or four cars were waiting. The few trucks—mostly construction vehicles coming the other way—threw handfuls of gravel at us and I wondered what our truck’s windshield was made out of as over and over it shattered the rocks thrown at it.

While we drove, we passed the time listening to our current audiobook, The Great Alone by Kristin Hannah—an appropriate choice as it’s a novel about a family that relocates to Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula, and we’d begun the book while we were there. Each chapter brought us a little farther on the seemingly endless road.

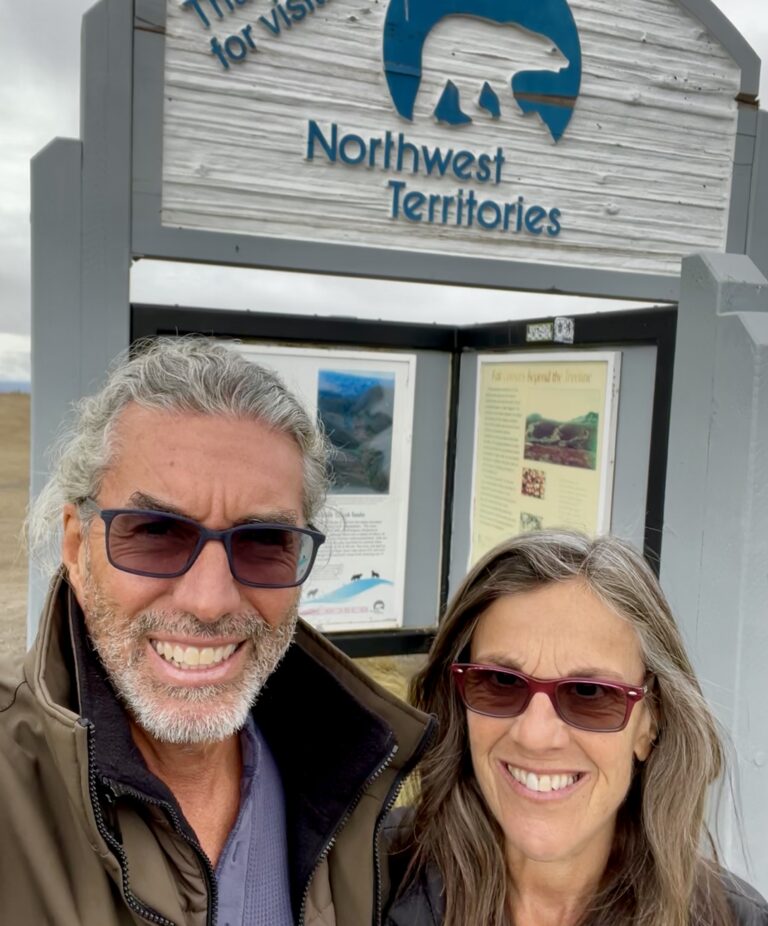

We soon arrived at our next border crossing—into the Northwest Territories. Though it felt a little anticlimactic after crossing the Arctic Circle, this was our fourth and the most remote province of the trip (after Alberta, British Columbia, and the Yukon) and it was deserving of a brief stop.

The signs at the border were in both English and Athabaskan, the language of the local Gwichʼin tribe. We were definitely in an area where what little population there was largely consisted of First Nation people. The population of the Gwichʼin who, along with the Inuit, are the most northerly indigenous peoples in North America, numbers between about 6,000 and 8,000 people across the Northwest Territories, Alaska and the Yukon. The Gwichʼin are highly connected to caribou, which provide their main source of food, tools and clothing. Their creation story tells that long ago, the Gwich’in and the caribou were one. When they separated into two beings, they became relatives and made an agreement—the land would sustain the caribou and the caribou would sustain the Gwich’in. Sadly, Arctic drilling and climate change now threaten that bond. We’d been told we were a little early but might get lucky and see the caribou herd migration across the Dempster. It’s a bi-annual event that usually occurs in the spring and again in autumn, but we were likely about 3-6 weeks early.

Though we hadn’t seen any caribou along the Dempster, we soon saw what was perhaps even more impressive. About an after we got back on the road, we noticed a (rare) car stopped along the side of the road and two women standing outside with binoculars. We knowingly pulled over to see what wildlife they may have spotted. They pointed to a spot hundreds of yards away where three grizzly bears foraged on berries, one bear bigger with gray on his hump back. We watched from our safe distance as they moved through the low bushes feasting on what would have to take them through the approaching winter. Oddly, it had warmed up to 65 degrees here, very unusual for the season.

After the grizzly stop, we fell into a steady pace as we continued north for hours and hours, taking in the scenery and musing about the other-worldliness of this place. We were north of the Arctic Circle in an exotic land of caribou and grizzlies that was nothing like either of us had imagined. Before we came here, we’d anticipated a long road through endless boring tundra. Instead we’d found a place of incomparable beauty at what felt like (and kinda was) the end of the earth.

We stopped twice during mid-afternoon for ferries. The first crossed the brown Peel River and was a small cable ferry but the second crossed the mighty Mackenzie River at its confluence with the Arctic Red River on a larger vessel. The ferries are both free and operate only in the summer months. In the winter, vehicles drive across the frozen rivers. The tiny town of Tsiigehtchic, a G’wich’in community of 138 people, is perched on a small promontory over the Mackenzie River. The locals are trappers and fishermen, along with craftspeople who sell their wares to the rare visitor.

By around 6:30 pm, we’d reached provincial park campground located about 5 miles south of the First Nation village of Inuvik. Though normally this would be a typical time to stop and set up camp, in this land-of-no-darkness it would certainly be possible to continue driving for a while longer. But from what we could gather, if we didn’t camp at the provincial park the only other option would be driving another 90 miles on the dirt road and camping at a tiny campground on the Arctic Ocean in Tuktoyaktuk at an excessive cost of $63 a night. And if somehow it were full, we’d have to backtrack to where we now were to find a camping spot. Most of the land for the rest of the journey north was First Nation land where boondocking was prohibited. We were excited to soon reach the Arctic Ocean but quickly agreed there was no need to rush. Plus the campground had free showers!

The campground was surprisingly busy with some locals having a large party along with a few scattered travelers like us. We’d completely lost track of what day it was but realized it was a Saturday and with the unusually warm weather it made sense that the locals would be out enjoying themselves. Fortunately, we found an available campsite on a small perch with a nice view located away from the partiers.

After settling in, we climbed a lookout tower that was at the campground for reasons unknown, took a much-needed walk (with bear spray) along a trail down to the nearby Mackenzie River, cooked dinner, then took wholly unsatisfying cool showers. It had been three days and we were ready for them, just not warmed up from them. The sky was clear and we’d read earlier that we’d have a chance to see the aurora borealis if the sky stayed clear, but clouds moved in by 9 pm.

Sunset wasn’t until around 11 pm and last light pretty much morphed into first light the next morning so sleeping would be hard tonight. From our campsite perch, we could just see the Beaufort Sea way in the distance. Tomorrow our dream would be fulfilled—putting our feet in the Arctic Ocean.