March 23, 2021

I woke suddenly at 6:00 am to a strong wind gust and rain slapping against the windows. The rain wasn’t supposed to start for five more hours, giving us time to get out before the road turned into gumbo. I listened and realized it was more wind than rain outside so I closed the windows, relaxed and enjoyed the protection of laying in our comfy bed in the truck, three feet off the damp ground and protected from all except a hurricane wind.

As the sun rose, it tried in vain to filter through the clouds but it was a dreary 40-degree morning, now with spotty snow showers along with the gusty wind. Around us, the higher mountains were receiving significant snow on their flanks. We’d packed up the night before and all I had to do was figure out how to turn the big truck around in the small space without getting us stuck on the steep ground that fortunately was not muddy yet.

A few minutes later, we were heading down the narrow rough dirt road to the wide rough dirt road, passing by dozens if not hundreds of campers in everything from tents to vans to giant RVs. A few were readying to leave as we passed them around 7, though many looked like they were taking advantage of the (theoretical) 14-day camping limit on forest service land. A half hour later, we turned onto the state highway where the 65-mph speed seemed crazy after crawling along at 10. Soon, we were on the interstate with its 75-mph speed limit. My 30-year old self would never believe I set the cruise five mph under the speed limit where even semis were passing us at 80. But it seemed the right speed after the dirt road, and there was little traffic. A short distance down the road, we stopped at a diner for a leisurely breakfast while we watched the light rainfall.

We’d decided to head south and hopefully avoid the worst of the rain and we mostly succeeded. As we drove, Susan explored online to see where we might go and we decided upon the Agua Fria National Monument where there were said to be Native American pueblo ruins. Susan was an archeology major in college so this was right up her alley. Recently, we’ve come to have a fondness for national monuments–typically, they’re almost as great as national parks but minus the crowds.

We set the GPS on my iPhone to find the entrance to Agua Fria and dutifully got off at the announced exit only to realize my phone has a real sense of humor. Suddenly, Apple Maps rerouted us and said rather than 10 minutes away, amazingly we were now an hour and a half from the entrance. We fired Siri (second strike—after taking us to the wrong trailhead yesterday) and tried Google maps, which laughed at how far off track Siri was. We followed the new voice that eventually found the right exit 15 miles away.

A nearby road sign basically said don’t go down any of the roads in the park unless you’re really brave or really foolish because no one maintains them and there’s no one to hear you scream. Having braved dirt roads in Baja Mexico, we knew it couldn’t be worse than those.

After about two more miles, we turned onto a rougher, narrow single-lane road that, after a few more miles, ended at a tiny circular dirt parking area with a sign welcoming us to Pueblo La Plata, a community of Native Americans that resided there some 750 years ago. Apparently we’d arrived, though all we could see around us was a sage and cactus prairie with some impressive rocky hills in the distance. We were the only car in the parking lot.

It was cool, cloudy, and drizzling lightly when we stepped outside, so we put on proper outerwear and made our way toward a mound in the distance. A lightly worn path led vaguely towards it.

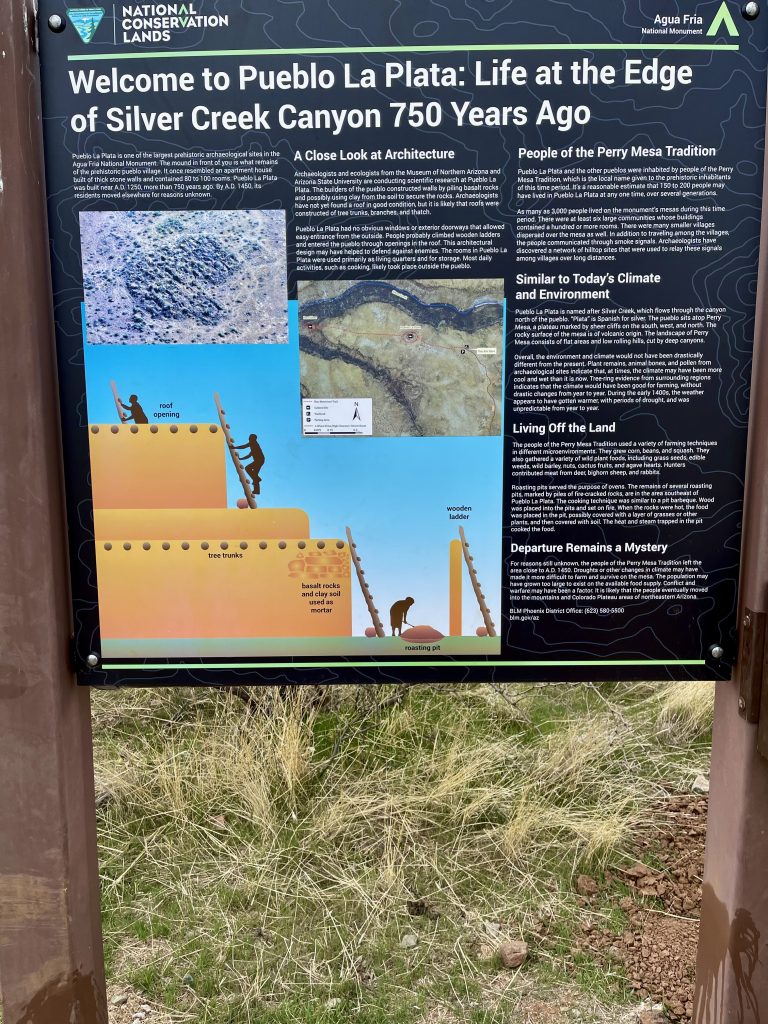

Our park brochure provided us with a guide that helped us find and identify the ruins. It explained that we’d be exploring the remains of a village consisting of a massive stonewalled pueblo which had nearly 100 rooms. Archeologists believe approximately 3,000 people lived in scattered villages around the mesa between 1200 and 1450 AD.

As we neared the rocky mound, we saw the roofless outline of the pueblo. The piles of rubble formed a large single-story “apartment” with dozens of rooms, some with doorways, made completely out of the large rough rocks that were everywhere. Because this was a seldom-visited monument, there were no fences, no “keep away” signs, roped-off areas, or blocked paths. We were able to walk right into the ruins whose walls were falling down but still had some semblance of rooms and doorways. A cold wind blew as we imagined the hundreds of people that once lived in the pueblo making dinner and chatting about the spring rains that were coming.

Hundreds, no thousands, of pottery sherds (an archeological term, short for potsherds) of all shapes and colors were everywhere on the ground. According to the brochure, pottery sherds around Pueblo La Plata consist of styles created locally, but also styles from distant areas, indicating this was not an isolated community. What was most notable was that the centuries-old pottery sherds and other artifacts, like carved obsidian, were simply laying all over the ground and on the structures instead of being on display in a museum somewhere. And even more remarkable was that they hadn’t been pilfered long ago by tourists. Either visitors have finally learned to leave no trace or (more likely) it’s just too hard to come down the long dirt road to this remote monument so tourists go elsewhere.

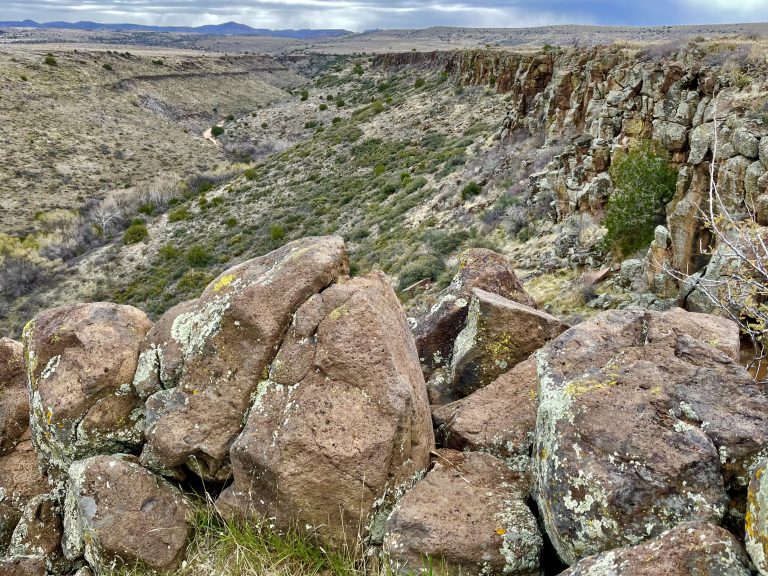

Another trail led away from the pueblo to the walls of a deep wide chasm with a creek hundreds of feet below, where the cottonwood trees were just starting to leaf.

How the villagers got the water all the way up from the canyon floor for hundreds of people was a mystery to us.

We followed a second trail led that away from the ruins for about a mile to a spot where two canyons met and the mesa ended at a point. Every step away from the pueblo meant more rocks strewn about, as the closer ones had all been gathered for building the pueblo walls.

At the point, we looked to the north and saw the snow-making clouds we’d seen earlier were headed our way. The wind suddenly picked up as the snow/rain hit us. We zipped up our coats and wondered how the pueblo residents had stayed warm. The only fuel for fires anywhere around were the few trees hundreds of feet down the canyon.

Back at the truck, we were glad when the heat came on, amazed by the resilience of the Native Americans.

We drove in the rain back down the long dirt roads toward the interstate and got back on the highway where semis barreled along at 85 mph. Our weather apps told us that the rain should let up as we went farther south. An hour later, it was still lightly drizzling when we exited the highway near Lake Pleasant in the far outskirts to the north of Phoenix.

We headed toward a place to camp on BLM land near the lake but soon learned that, like Apple Maps, Google Maps has a sense of humor, as it told us to turn to the right off of a washboard road that would have put us in a ditch. No turnoff existed anywhere near there. So, we tried GAIA maps (our hiking app) and it was just as confused.

We decided to keep going up the road past the phantom lake turnoff to see what we could find. Normally, this close to a big city such as Phoenix we’d expect there to be a lot of cars, trucks and ATVs on the road, but it was a Tuesday afternoon and it was still spitting rain.

We were almost alone on the road. Along the way, we saw a couple of herds of wild burros on the roadside who stared as we passed.

After a few bone-rattling miles, we came to a private property sign, so we backtracked to a potential campsite we’d seen just off the road.

The campsite was up a short steep hill that necessitated 4wd to access. It was level and surrounded by cholla cactus, with thousands of tall saguaros dotting the hillsides.

After a short exploration, we returned to the truck and found that the bottom of Susan’s hiking shoes were covered in cholla spines. Not only are they needle sharp and barbed, but clusters of them that fall on the ground as seed carriers have a sticky glue on them. One way or another, they will attach if touched.

Susan gently picked off one tennis-ball sized cluster and tried to fling it away, but eight of the sharp spines instantly impaled her finger, some going in a quarter inch deep. I broke out the pliers (the only way to get the tough barbed spines out) and Susan painfully removed the spines. Susan doesn’t like unqualified medical personnel to treat her so she bandaged up her finger herself afterward, using her remaining nine.

But, the campsite was a looker. Gazing one direction, we could see giant Lake Pleasant a couple of miles away, and the other way gave us views of soaring jagged mountain peaks. There were no bad views.

The remains of the clouds, now pink as they hung over the hills, ensured another beautiful desert sunset. The burros brayed to each other in the distance as the wind blew and it looked to be a peaceful night.