March 29, 2021

We left the hotel in Albuquerque feeling clean and rested. A short drive brought us to nearby Petroglyph National Monument. We decided to check out Boca Negra Canyon, which is part of the national monument but, oddly owned and managed by the city of Albuquerque.

The road to Boca Negra goes through residential areas that are visible from the Monument, giving the area a unique urban feel. We hiked up the Mesa Point Trail to view the petroglyphs but were underwhelmed after just seeing the ones at the much more extensive and wilder Three Rivers Petroglyph site yesterday

Leaving the Albuquerque area, we climbed along highway 550 into beautiful mountains. It was quite a change from the desert scenery we’d been immersed in since the trip began. As our elevation increased, we left the desert tumbleweed and cacti behind us and emerged in a scenic mountain area with pine trees, rocky outcroppings and rushing creeks.

Susan had found a trail to Spence Hot Springs, just off the highway and we stopped for an early afternoon hike into the mountains. The trail led down to and across a small creek, then climbed steeply up into a boulder-strewn area where there was a natural pool large enough for several people to soak.

We joined a few others there to soak our feet and enjoy the views. There were two twenty-something women in the pool and we struck up a conversation with them. When one, Pamela, told us she lived in Princeton, New Jersey, Susan mentioned that one of our son’s girlfriends is also from Princeton. Princeton is a small town and it turned out Pamela not only knew her but they had taken ballet classes together. Pamela also confirmed what we already knew—that our son’s girlfriend is a total sweetheart. We were amazed that a random traveler in a remote New Mexico hot spring off of a lonely highway was connected to us this way.

As we were sitting on a rock drying our feet, we heard voices a few feet from us coming from a small cave where the water was coming out to fill the hot pool.

Suddenly, a man, a woman and a child squeezed through the small opening from the cave that apparently opened into a hot spring cavern inside. We weren’t sure we’d want to be soaking inside the dark cave, especially when the view in the outer part was so spectacular, but they seemed to enjoy it.

Back at the truck, we drove a little farther to Jemez Springs Trail but we were too early in the season and the trail was impassable due to snow. Though we were just wearing shorts and hiking shoes (we hadn’t even brought hiking boots on this trip), we briefly trudged through a little snow to see the creek at the beginning of the trail before turning around.

We continued along the highway, steadily climbing into the mountains. Soon, there was significant snow along the road as the temperature dropped and wind picked up.

The road eventually leveled and brought us to Valles Caldera National Preserve. We drove along a snow-lined dirt road into the preserve, crossing clear streams and briefly explored. Over a million years ago, a huge volcanic explosion created a 13-mile wide depression and the Preserve is considered the world’s best example of an intact volcanic caldera.

The area is now known for its pristine trout streams, abundant wildlife and, because the ancient volcano blew its top, a unique plateau-like flatness at an elevation of 9,000 feet. Sadly, the area was clear-cut of all old growth trees in the late 1960’s but now as a national preserve, the forest is returning. It was cold and windy in the caldera and the roads were muddy from recent snowmelt so we didn’t stay long but discussed returning to the caldera one day in warmer months to explore its unique beauty.

Leaving Valles Caldera, the highway dropped in elevation to about 7,300 feet as we headed to our next destination, Los Alamos, the birthplace of the atomic bomb. The relatively modern small town came into being during World War II when the U.S. government bought up all the ranch land around Los Alamos using eminent domain, secretly established the area, known then as “Code Y,” and began the Manhattan Project. The government brought J. Robert Oppenheimer, hundreds of other talented scientists and engineers, and thousands of support personnel to Los Alamos to build Fat Man and Little Boy, the first (and fortunately only) atomic bombs used in wartime.

As we drove down a hill toward Los Alamos, we saw the small town in the near distance. But instead of bringing us there, our GPS somehow directed us to a very official looking guard station. I rolled down the window and asked the unsmiling guard how to get to the town but he informed us simply that we had to turn around and go back from whence we came. There was a lot of firepower visible (and likely more not visible) so we did as instructed.

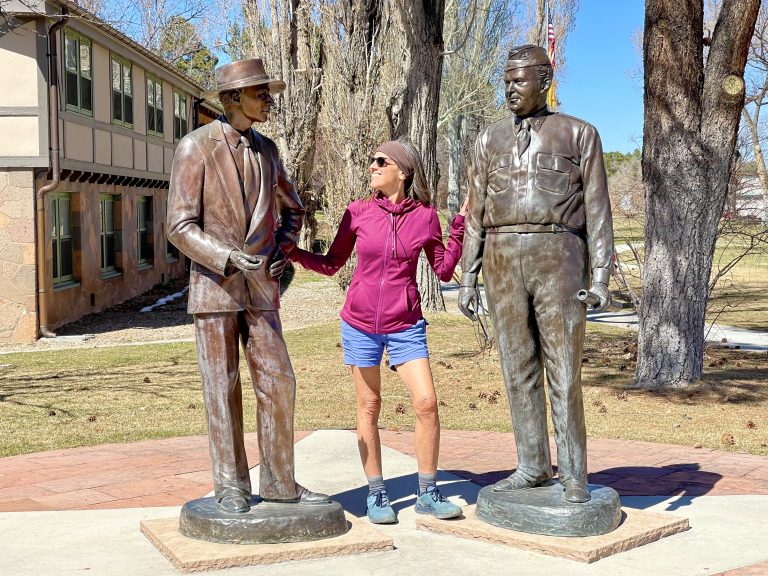

A few turns and several roundabout miles of driving later we eventually found the main part of town.Aside from a few historical markers, including historical bronze sculptures of Oppenheimer and General Leslie Statues in a city park, the town felt quite sterile and not particularly visitor-friendly, though it did look to be a prosperous town.

Los Alamos, it turns out, has the highest millionaire concentration of any U.S. city, with over 12 percent of households worth at least seven figures. The poverty rate is half the national average. There’s some serious money in nuclear physics.

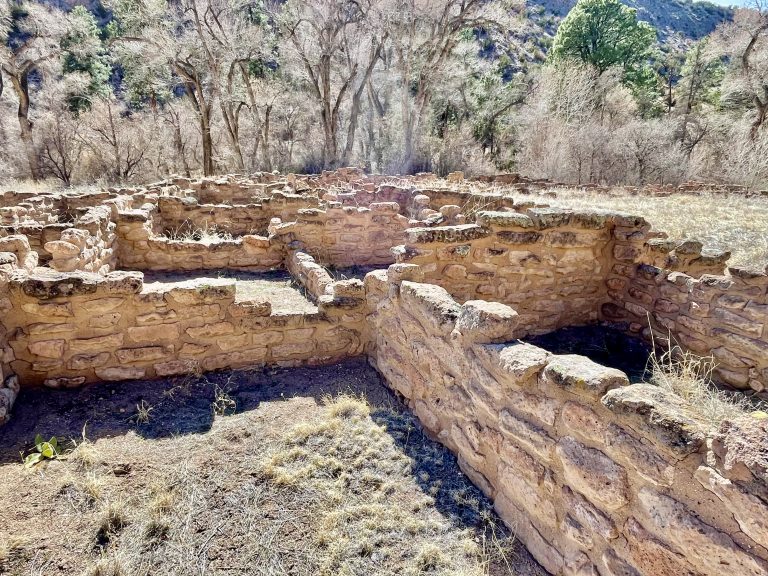

Leaving Los Alamos required heading out on another circuitous route, but eventually we found our way back to the main road. Our next destination was the oddly named Bandeleir National Monument, about a half hour away. Named for a Swiss anthropologist, the Monument features ancient pueblos that date between 1150 and 1600 AD. It has cliff dwellings similar to the ones at Mesa Verde National Park, but with far fewer tourists.

As we approached the Monument, we climbed in elevation again and the mountain views were spectacular. There was a light dusting of snow and more in the distance. The Monument’s elevation ranges from 10,000 feet down to about 5,000 feet. The cliff dwellings are at the lower elevation and when we arrived in the late afternoon it was comfortably in the 60’s.

It was a Monday and only a handful of other cars were in the parking lot of this off-the-beaten-track Monument. We followed a one-mile path that led up to numerous structures that once were part of long houses built into the sandstone hills and caves. The trail also passed a large circular kiva that was used by the Pueblo people as a communal meeting place.

Fortunately, the Monument was not over-loved like Mesa Verde, so visitors were permitted to fully explore with very few restrictions. We climbed timber ladders up and into some of the structures. While not exactly cozy, the inhabitants were well-protected from weather and even invaders, tucked up into the caves. A clear stream flowed near the pueblos and life would have been good here until settlers arrived in the 18th century.

We decided to camp for the night at an inexpensive and uncrowded campground near the entrance to the Monument. After dinner, we walked up a trail outside the campground and watched the sun set into a pink and orange sky.