February 10, 2021

We both slept warmly last night despite the cold temperatures outside and were greeted by the sun coming up behind us. Sometime in the night I was awakened by coyotes howling, something I always find particularly enchanting. All the slushy puddles around us from the night before were frozen solid as was the long snow patch on the way down from the steep hill, but with our capable truck we made it down with only a few apprehensive moments.

Within minutes, we were again on highway 395, which must be one of the top five prettiest roads in California especially in winter as it parallels the snowy Sierra Nevada and White Mountain ranges. Our eventual destination for the day was Alabama Hills—where we’d camped once before and knew we could find a scenic, boulder-strewn campsite at a lower (read: warmer) elevation. Meanwhile, there was a vast snowy wonderland to explore.

Beautiful, and mostly frozen, Mono Lake came into view just a short distance down the road

Susan remembers Mono Lake from her backpacking days during college when she stumbled upon a “Save Mono Lake” festival along the lakeshore. Conservation efforts that began at the time of the festival in the late 1970’s helped prevent the lake from disappearing after the City of Los Angeles had started to divert the water for its use.

Just past Mono Lake, we passed the (closed for winter) Tioga Pass turnoff at Lee Vining that leads into Yosemite. We’ve taken that incredible road before and undoubtedly will again, but today it wasn’t an option and we were heading farther south.

The mountains become even higher to the south, making the drive even more spectacular the farther we went. As we ascended even higher, the temperature dropped. The highway, plowed but with several feet of snow piled up alongside, twisted through high foothills until it eventually opened up and climbed to 8,000 feet before descending a bit at Mammoth Lakes.

We turned off the highway and drove the couple of miles to the town, which was still partly open because of the skiers and snowmobilers who visit in winter. After a takeout coffee and breakfast run, we left town headed south again.

So we wound our way up the snowy Sierra mountainside and just ten minutes later we’d arrived. Convict Lake, located at an elevation of 7,850 feet, got its name as the result of a classic Western story. In 1871, a group of convicts escaped from prison in Carson City and took refuge near the lake. A posse came after them and a shootout ensued. It didn’t end well for the convicts – those who didn’t die in the shootout were eventually captured and hung.

Large snowbanks initially kept the lake hidden from view but the lake’s location beneath the enormous snow-covered peaks was obvious. We climbed over the piles of deep snow and made our way to a path of semi-compressed snow at the lake’s edge.

The serene scene was interrupted only by the sound of skates scraping across the frozen lake. We watched as the only other visitor set up a tripod to record her figure 8’s, loops, and jumps.

When we trudged through the snow and came closer to the lake, the skater approached and warned us about the large areas of cracked ice near the lake’s edge. A brief conversation with her revealed that she was a professional skater on a journey from Colorado with the goal of finding the best frozen lakes on which to skate.

I gingerly stepped onto the ice and, hearing no cracks, executed a near-perfect pirouette while Susan stayed back to photograph the event.

Leaving the lake, we continued south down Highway 395. About an hour later, we saw a small sign for the Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest that pointed to the east, across the wide valley from the Sierra and into the White Mountains. We’d been wanting to venture into the White Mountains, if nothing else because they were constantly overshadowed up by their showy Sierra neighbor across the Owen Valley. The Sierra range is high and jagged, gets huge amounts of snow in winter and even has the southern-most glaciers in North America. The White Mountains, on the other hand, are not quite as tall and only get what little snow the Sierra doesn’t hog as winter storms move east. There are few roads into the White Mountains. We’d both heard of the bristlecone forest but thought the road to it must be closed now because of snow levels at such high elevation. Surprised to see the road was open, we made another split-second decision and turned onto the road that eventually took us far beyond what could be seen from the highway.

Initially, we climbed steadily through high desert scrub (the fairer Sierra across from us was full of beautiful pine forests) twisting on a decent two-lane road until we turned onto a smaller road. We followed the road ever higher until, to our surprise, we found ourselves in a pine forest tucked so far back into the mountains that we could no longer see the valley below. The White Mountains were definitely more intriguing than we’d anticipated.

We stopped to check out an overlook and discovered the temperature had gone from 60 degrees less than an hour ago in the valley to 32 degrees. We were amazed to be at 9,000 feet and nowhere close to the top—and doubly amazed that we were driving at this elevation in mid-winter.

At the higher elevation, long patches of snow and some ice clung to the road, particularly in shady areas. We were lucky to be here between snowstorms. As the road twisted and turned, the White Mountains repeatedly surprised us and graciously presented us with incredible views of the snow-covered Sierra far across the valley, but now from a much more similar elevation.

We could see the spine of the Sierra marching from well north of Lake Tahoe, near where we’d crossed the day before, to as far as the eye could see, well south of Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes. To the south, we could also see a mountain range about 50 miles away where Death Valley begins.

The road got steeper and climbed ever higher through beautiful pinyon pine forests and finally into ancient bristlecone pines. After about an hour, we came to a ranger station near the oldest trees. We got out, bundled up and hiked up a trail through the old trees.

The ancient gnarled trees on the dry hillsides looked half dead but still had new growth. Bristlecone pines are the oldest species of tree in the world, and this forest contained the oldest of all bristlecones—nearly 5,000 years old. Many of the bristlecones we saw on the trail were seedlings around 2,000 BC.

Bristlecone pines are a rare species that can be found only at a few high elevation locations including this one in California and at locations in Utah and Nevada. We realized that we had now seen the rare bristlecone pines in each of the three states—we saw them on our hike several months ago at Cedar Breaks National Monument in Utah, we saw them a few years ago at Great Basin National Park in Nevada and now in California. We also realized that just a few weeks ago we’d been on the western side of the Sierra range where we’d seen the largest trees in the world (sequoias) while here in the “forgotten” White Mountains we were seeing the oldest.

We felt like we were at the top of the world. The view was fantastic and we didn’t want to leave. When we finally did, I turned back up the road we came in on to try to go even higher, but it quickly became unpaved, and worse, unplowed. Perhaps sometime in the summer, we thought. We noted several good places to camp on the way up and because most people choose to explore the Sierra, we felt that many fewer would crowd into the “homely” stepsister.

Be the time we’d returned to highway 395, we’d lost 6,000 feet in elevation and gained 40 degrees. Alabama Hills was only a couple of hours farther away, which is why we had time to spend at Convict Lake and in the White Mountains. We find in our travels that not being rushed is the key to flexibility. A trip should be about intentions, rather than plans.

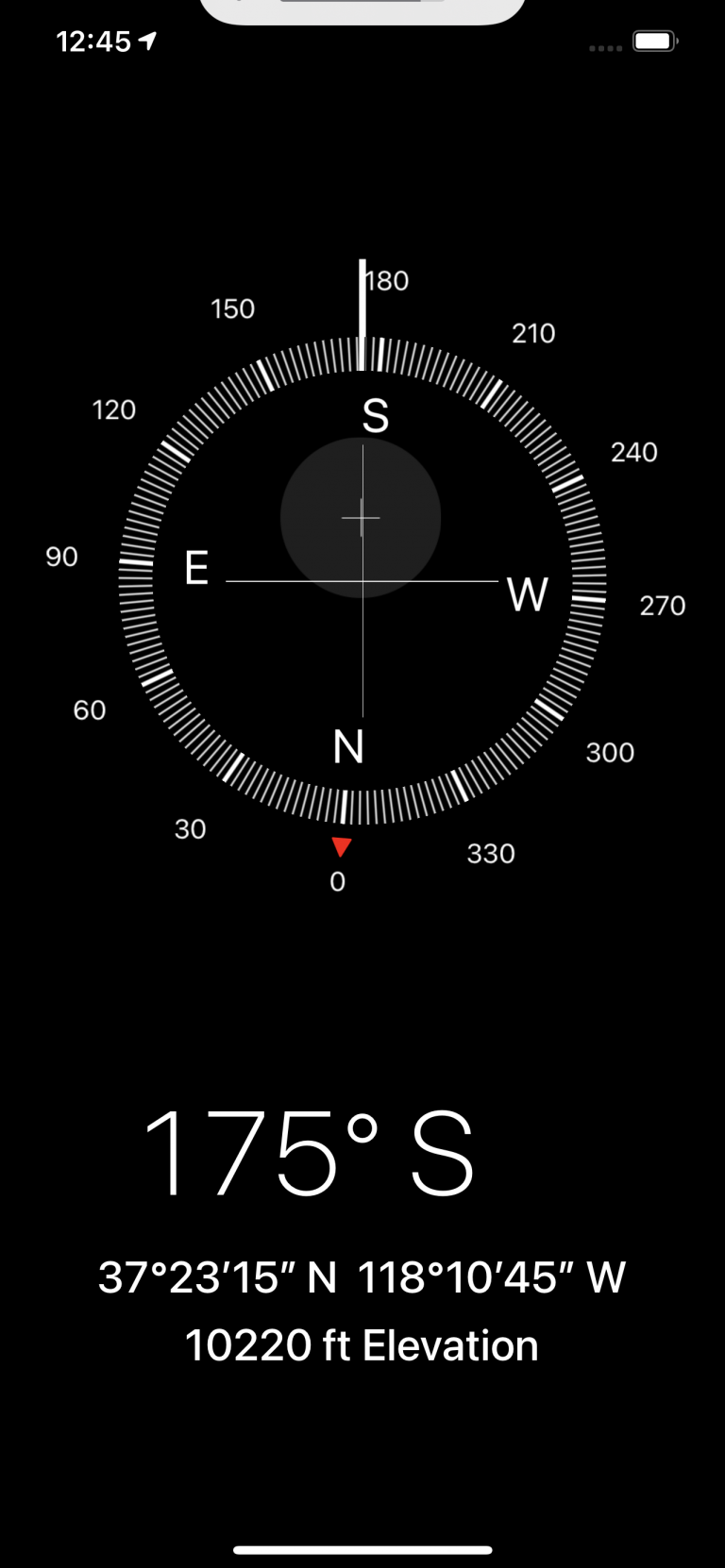

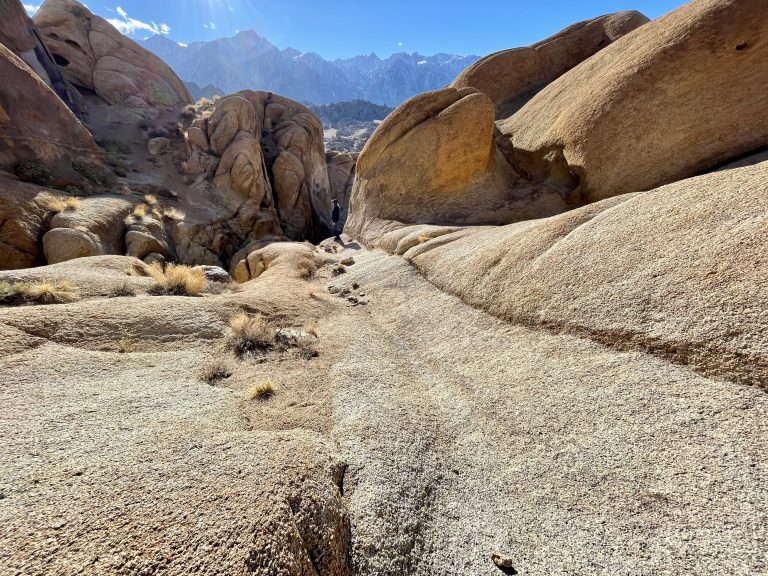

Two hours farther south, the White Mountains became lower and less grand as they descended toward Death Valley, while the Sierra Nevada mountains became higher and even more grand. We turned west off Highway 395 at Lone Pine near the base of Mt. Whitney in the Sierra range. Mt. Whitney is the highest mountain in the contiguous lower 48 states at 14,500 feet and looms over the huge collection of odd smooth boulders and enormous rock formations known as Alabama Hills at the base of the mountain.

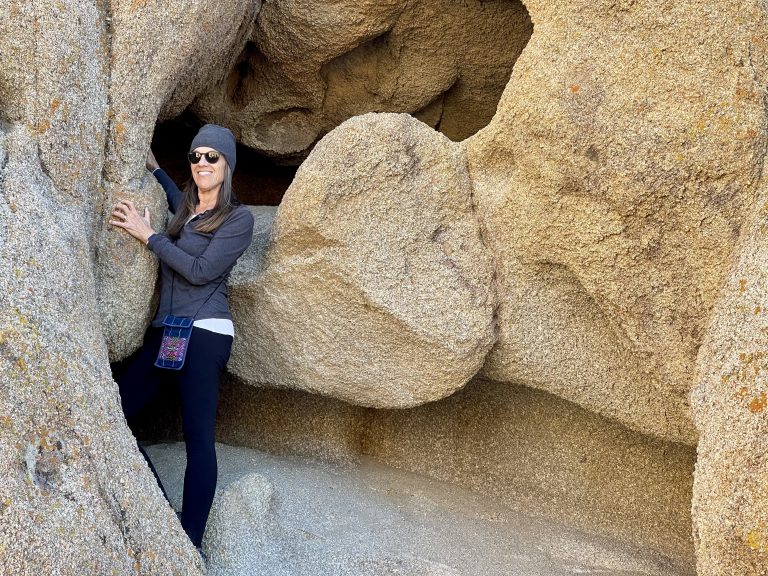

Alabama Hills is situated on BLM land, which meant we could follow some dirt roads and pull off pretty much anywhere to camp for free, under the watchful eye of giant Mt. Whitney. Many westerns and some sci-fi movies were filmed in Alabama Hills and there always seems to be a strange familiarity to them, probably from watching old movies.

Oddly, much of the land near Alabama Hills is off limits and is owned by the city of Los Angeles, a couple hundred miles to the southwest over the mountains. Although conservationists had been able to save Mono Lake, Los Angeles successfully confiscated the entire Owens River watershed so it could be sent to thirsty golf courses, swimming pools and housing developments. It seemed strange and somehow unfair that a far-off city could take the clean natural water that flows from the ice fields of Mt. Whitney so Angelinos could water their lawns.

Soon, we found a site next to a 400-foot-high sandstone formation with a spectacular view of the mountains. We wandered on foot to explore the hills around us in the 60-degree sunshine.

Afterwards, we watched the shadows creep towards us as the sun set early due to the proximity of the mountains, prompting an early dinner, accompanied with a cold beer.