February 5, 2022

The next morning, we had a decent breakfast at the small hotel, included in the US $30 room price. Our clothes had finally dried (though most smelled like mildew and went back into the laundry bag) and we had a couple of hours before we had to leave for our flight to Lima.

We walked farther into the city to the Belen neighborhood so we could check out the Mercado de Belen. The huge open-air market was noisy and busy with vendors selling every kind of food and non-food item imaginable.

Block after block vendors set up their stands on a large closed street, some sections so jam-packed with people there was barely enough room to walk.

The market spilled over into side streets with tuk tuks and motorcycles vying for space. The scent of raw meats and fish, caiman skins, large open buckets of spices, fruits we’d never seen before and a good amount of rot filled the humid air as packs of dogs patrolled, looking for scraps.

We didn’t stay long, as mask-wearing was nominal and it felt like one of the most Covid-unsafe places we’d been in the past two years.

As we left the market, the (mostly outdoor) shops continued as we headed through the commercial district. Vendors and stores were selling goods ranging from bulk quantities of beans to transistor radios. One storefront called itself American Brands but upon peering inside we saw it held no brands we’d ever heard of.

We wound our way back to the hotel, past hilly roads leading down to the riverfront shantytown of Belen. Unlike the poor but cheerful residents of the tiny jungle town of Oran we’d seen the previous day, the locals in Iquitos, and the poverty-stricken barrio of Belen in particular, smiled infrequently and seemed to be worn down by their abject poverty.

Jón, who’d lived in both Oran and Iquitos, had told us that although Iquitos had lots of amenities nonexistent in Oran (like power lines, adequate fresh water, high schools, and internet), life in Iquitos was in many ways more difficult. In addition to struggling with extreme poverty in Iquitos, its residents had to tolerate the constant noise and smoke from motorcycles and tuk tuks, lack of sanitation, and high unemployment. And Covid had hit the city much harder than most of the world—the death rate in Iquitos contributing significantly to Peru having the highest reported Covid death rate in the world. The Amazon may be considered the lungs of the world, but the lungs of its residents couldn’t be saved during the pandemic due to overcrowding and lack of adequate healthcare, equipment and supplies. Undoubtedly, the limited mask-wearing (and probably limited mask availability) at the market didn’t help matters.

Back at our room, we packed up and went downstairs to ask the front desk person to help us hail a taxi to the airport. He looked concerned and said there were very few in the city but he’d make some calls. We told him never mind we’d just take a tuk tuk (which were plentiful) and he casually warned us only to get in a newer one as the older ones probably had no front brakes. At that moment a man walked in and greeted the owner. He happened to be a taxi driver and offered to take us so we loaded up into his battered old Toyota wagon. Once underway, I could hear the rattling suspension and grinding brakes—likely no better than the tuk tuks we were warned about.

En route to the airport, we learned that in the streets of Iquitos, as on the sea, tonnage rules. Motorcycles were forced to give way to larger tuk tuks, who were likewise forced to yield to cars. The few large trucks on the crowded roads drove with impunity, at the top of the vehicle food chain.

The airport was half the size of the one in Leticia and had only two gates, even though Iquitos was 10 times as populated. Most people boarding our flight were taking selfies or making videos as their families climbed the stairs into the plane, making us think this was the first flight for many of them. Given the poverty level in Iquitos, we assumed flying was a major luxury here, even if the flight prices were relatively cheap for us.

Once everyone was seated, an airline employee with a bright green vest came to our row, asked Susan her name, then pointed to me and motioned for me to come with him. As I went up to the front of the plane with him, he handed me a green vest to put on and asked me to follow him back down the stairs off the plane. Warily, I stopped at the top and said he’d need to tell me why before I’d take another step. The man said in broken English there was some kind of irregularity in my checked bag. I glanced back at Susan, who was out of hearing range. Her eyes were wide, wondering where they were taking me.

My mind raced; what was in there? I’d been traveling with my pocket knife, but it was allowed in checked bags. I felt like all the other passengers were watching me as I deplaned with the green-vested man and joined multiple additional green-vested staff who escorted me a quarter mile away across the hot tarmac to a building. By now I figured Susan was frantic and I was getting a little worried myself. But I’d been through similar situations years before in Central America and knew not to panic—yet.

Six employees stood around my suitcase and one woman among them who spoke a little English demanded I open it. I asked why and was shown a photocopy of an X-ray of a prohibited item—the portable battery used for charging our devices off-grid that I’d bought just for this trip. Damn. I usually carried it in my backpack on the plane but it was heavy and I had forgotten to transfer it back after using my pack while we were in the rainforest. Los sientos, I said, and stated that I’ll just put it in my pocket and be on my way. No, señor, no permiso. Hmm.

Then they asked for my passport, which I explained wasn’t on my person by pointing to the plane—where it was safely in my backpack. Then I remembered that, thankfully, I had a photo of it on my phone. They took a look and jotted down some information on a form. I asked for the battery pack again but they refused unless I exited the airport and returned with it through security—at which time the plane would already be gone. But, it already went through security (there’s an X-ray of it!) and it’s the same as if it were in my backpack, I argued.

No amount of logic would work and I knew I was holding up the entire flight so I signed a form, donated my battery to the airline (or, more likely, to the employees who confiscated it).

A hundred Peruvian faces watched me through the windows of the plane as I made the long walk of shame back across the tarmac and climbed the stairs. Stupid gringo. It wasn’t until I was back in my seat that I noticed the frantic texts Susan had sent. She’d had no idea where they had taken me, why, and whether I’d be returning to the plane. But now all was well and the plane soon lifted off, its weight reduced by one apparently dangerous portable battery pack.

We flew from the Amazon rainforest to the coastal desert city of Lima and the change was astounding. Going from muggy, hot and poor to dry, cool and wealthy took an hour and 45 minutes. Leaving the jungle, I had a pang of missing it already. It was harsh and wild but it was beautiful and filled with some of the kindest people we’d met and the most exotic flora and fauna we’d ever seen.

The first thing we discovered in Lima was that, while still relatively cheap, prices were much higher than anywhere we’d been in the past month. The Uber ride from the airport was $10 to our inn, at least twice what we’d paid for a similar length ride in Colombia.

Along the drive, we admired the city built along the Pacific coast, with the blue ocean next to the beaches and desert mountains in the distance. It was quite beautiful and reminded us a little of Southern California. We were staying at a bed and breakfast Susan had found us only a couple of blocks from the coast in a quiet neighborhood in the upscale Miraflores section of town. The delightful weather was was in the 70’s and dry with an onshore breeze blowing gently.

After we checked in, we walked around the area, and marveled at how neat and well-maintained everything was. It was a reverse culture shock coming from the poverty-stricken part of Peru we’d just left. There were heavy Covid restrictions everywhere, including mask requirements even outdoors, double masking indoors, and no entry to anything anywhere without a vaccination card showing three shots (including the booster).

After showing our vaccination cards and donning multiple masks, we wandered around upscale oceanfront outdoor Larcomar Mall, near our B&B. It was lovely but we felt out of place—not because we were Americans but because we were still in Amazon jungle-mindset. In fact, the mall atmosphere made us feel like we’d just been transported back into the U.S. About half of the shops and restaurants were U.S. or European chains, including Adidas, Boss, Calvin Klein, Colombia Sportswear, Guess, H&M, The Gap, KFC, TGI Fridays and Pinkberry.

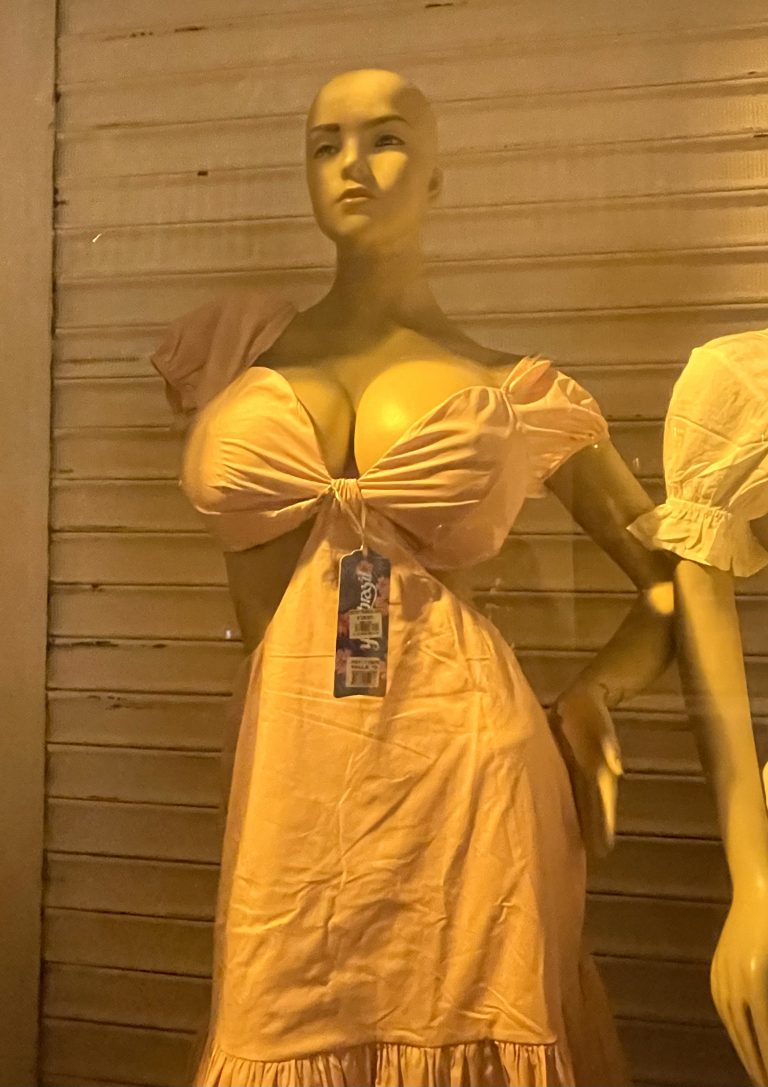

One store window display jumped out at us. Unlike the very buxom mannequin we’d see in a Cartagena storefront, here a mannequin had just the opposite physique. Clearly Colombia and Peru have different standards of feminine beauty.

We knew that Lima was known for having the best food in South America and wanted to try some local dishes, so we splurged on a meal that was definitely overpriced for Peru. I had a delicious lomo saltado, a very popular dish of strips of sirloin with peppers and onions on top of French fries with two quail eggs crowning it all. Susan enjoyed a locally caught seafood entrée, now that we were back at the ocean. We also ordered a pisco sour, along with a mango version of one, made with a popular Peruvian liquor.

After dinner, we took a short stroll along the waterfront promenade. We were treated to a beautiful view of a huge 65-feet tall illuminated cross on a hilltop with its long reflection in the Pacific Ocean. The cross, we learned, was built in 1928 and is the destination of pilgrimages during Holy Week between Palm Sunday and Easter. Made of steel and concrete, the cross has withstood three significant earthquakes over the course of the past century.

After our long day, we headed back to our hotel where we’d sleep in a quiet, climate-controlled room with hot running water and multiple outlets to charge our devices. But no battery pack.