September 2-3, 2021

We waited in the hotel room for the rain to stop, then packed the truck for the next adventure, to a place we’d been unable to see the last time we were in the area. Last spring when we were traveling through New Mexico we planned on heading to the Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness, also known as the Bisti Badlands. Bisti is a rarely visited and remote BLM area said to have unusual sandstone formations. I was having bad neck pain at the time and we decided to head home instead, disappointing us, especially Susan who’d been excited by the description and photos of Bisti. But now, Bisti was only an hour away and we headed down the rough highway (so far New Mexico had the award for worst paved roads of any state where we’d recently traveled) to a dirt road that would take us into the Badlands.

Three miles down the desolate dirt road, we suddenly saw a man sitting in a folding chair at the side of the road in the middle of nowhere. He waved us over and asked if we were part of the film crew. Uh, no. He then told us we’d almost reached the parking area (where we would see the film crew).

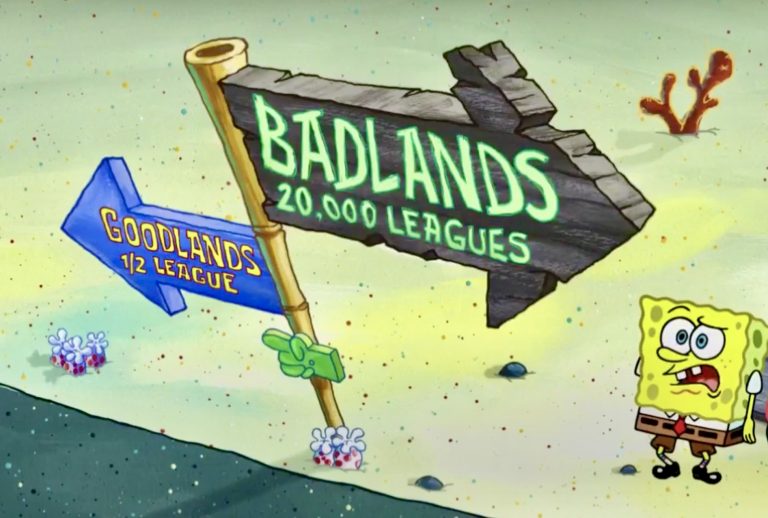

We soon came to a small lot that was almost full of commercial vehicles. We couldn’t help laughing when they said they were a production crew filming a live-action portion of a new SpongeBob movie. They also laughed and said no when we asked them if they needed any extras (Them: You don’t have a couple of yellow suits with you, do you?).

We had a quick lunch, then 25 feet beyond the picnic table a sign said that said we were officially entering a wilderness. In the distance along a low light-colored plain were some low hills with formations that we soon discovered couldn’t be see until you’re in them. Bisti has no trails, rather you simply walk across the sandstone ground until you find something interesting, which is what Bisti is full of.

It was good we waited until today to see the place because the flash floods had just (mostly) dried up and the whole area was wiped clean of footprints and looked like a proper wilderness. Tiny rivulets from the receding flood flowed into larger ones and eventually into a ten-foot wide sandy wash, which still had enough water in it that we had to go around it.

After a mile of wandering on the sandy plain (I’d turned on my GPS so we could find our way back in case we got lost), we found a bizarre-looking section of 50-foot-high sandstone hills that had eroded into small canyons we could barely walk through so we climbed into them. Eons of rain and wind had eroded the whole place into fascinating shapes.

We climbed up into the trail-less area farther and wandered around the weird shapes and colors. Most of the sandstone was brownish gray but some protruding areas were red from iron and black from millions of tiny bits of coal. It was only 75 degrees out but we were hot from walking in the blazing sun until a breeze picked up. We saw only one other person who went to the first formation, snapped a picture and left. Our timing had been good as the muddy areas were mostly dried up and we could climb among the miniature canyons in the larger formations.

We wandered farther and were amazed at the odd shapes and colors, many in the shape of hoodoos, tall thin spires of harder sandstone. Some are made of softer sandstone with harder rock on top giving them a mushroom appearance as the softer part weathers faster.

It was obvious from the washes that the formations quickly eroded into the plains after storms and would someday be flat. But because we were in a desert, the lack of frequent rain would keep the place weird for a long time. After a few hours, we hiked back to the truck glad we’d finally seen this odd place.

Our route brought us through many miles of Navajo Reservation land, most of it beautiful and stark, and completely unusable. In the rare spots where there was water, the Navajo had small developments of manufactured homes that at least had spectacular views even if there was literally nothing around them for hundreds of miles. It was appalling to see how, long ago, the U.S. government had screwed the Native Americans, pushing them onto land that is almost completely uninhabitable desert.

Eventually, Susan directed us down a dirt road into BLM land where our iOverlander app indicated there were some nice places to camp.

Coming down one sandy section toward a wash, we stopped abruptly where suddenly there were two traffic cones – and no road!

The recent heavy rain had washed out the road and before us was a five-foot drop-off into what was normally a dry wash but was now a muddy river. On the other side of the normally dry wash, now a fifty-foot-wide shallow river, there were glaring headlights of a parked vehicle. We figured they must be stranded there due to the collapsed road/now raging torrent, as our map showed there was no other means of ingress or egress. We’d intended to cross the wash to the best camping areas but that was obviously not an option.

Just to our right was a large flat spot that, while not as remote as we liked, looked inviting enough and there we set up camp for the night, pleased we’d once again fall asleep to rushing water. We thought.

Around 8:00 pm, just before the sun fully set, we hiked up the steep hill behind our campsite. From the top we could see the vehicle with the headlights more clearly–it was a truck with a very large fifth-wheel RV attached. We quickly surmised that the people in the RV must have been camping on the other side of the wash for a few days before the rain. Taken by surprise or not realizing the power of flash floods, it was too late once they decided to leave, as the wash was an impassable raging stream. We hoped the truck would turn off its headlights so they wouldn’t shine on us through the night.

While we were up there, a Jeep zoomed toward across the flooded wash from where the RV was. The Jeep just made it through the water before it scaled the collapsed hillside up to the dirt road by our truck then disappeared up the road. It was obvious that the truck with the RV could never make it across the “river.

Shortly after we returned to our truck, a pickup truck came down to the spot where the road abruptly ended, parked there, and the driver got out. Then a man (presumably from the RV) waded across the waist-deep water from the other side and met up with the pickup truck driver on our side. The truck then left and the man walked back across the wash to the RV. We thought nothing of it and climbed into bed in our truck, hoping for another peaceful night.

About an hour later, the pickup returned with a very large front-end loader following behind. By now it was around 11:00 pm and the show was about to start. There was no cell service where we were so either the Jeep driver or the pickup driver must have gone into town to make a phone call, which resulted in the calvary coming out.

For some reason (probably overtime pay for the state employed front-end loader operator, we guessed), someone decided 11:00 pm was a good time to start working on creating a new road across the wash. For hours the loader worked, digging a path into the water, often only 50 feet from us, occasionally leaving to get a bucket-full of sand to spread.

There was no way we’d be getting much sleep tonight due to the constant diesel engine growl and frequent beep-beep-beep when the loader reversed. Sometime before daybreak, maybe around 3:00 am, the (well-paid) state employee roared off, apparently finished and we finally got a little sleep. It didn’t last long.

Just as the sun rose, we heard a vehicle start and looked out to see the truck with the RV slowly making its way down the dirt road on the other side of the wash. At least we’d get to see the climax from last night’s noisy construction. The driver sat in the truck looking at the new road, still with three-feet deep water over it. I could almost hear him say, screw it, as he revved the engine and powered across the water, at one point almost getting hung up on something. Then he roared off up the road on our side of the wash and up the road into the sunrise.

Not long after, an ATV came down the road on our side and stopped maybe 20 feet away from our truck to check out the wash. We chatted with him briefly and learned that he gave ATV tours and was there to see if he’d be able to cross the wash yet. He then shared some tips with us about places to explore nearby.

We stopped and took a short hike in the Kaibab National Forest to LeFevre Overlook. The view from the overlook reveals the entire expanse of the Grand Staircase National Monument. Grand Staircase is a massive sequence of rock layers that extends for hundreds of miles and includes Bryce Canyon National Park, Grant Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Zion National Park, the Colorado River and even Grand Canyon National Park.